This page is part of our free feeds & speeds master class.

FREE FEEDS & SPEEDS MASTER CLASS: Learn What the Experts Know >

Key Takeaways

Here's a good video overview of Climb vs Conventional Milling (Down vs Up Milling):

Source: My CNC Chef monthly column with Cutting Tool Engineering Magazine

- Climb Milling = Down Milling

- Conventional Milling = Up Milling

- Manual Machinists should stick to Conventional Milling because backlash makes Climb Milling dangerous.

- CNC Machinists should know that there are times to use the climb milling process and there are times where the conventional milling process works better.

- Conventional Milling:

- Upward forces tend to lift the workpiece during conventional milling.

- Conventional milling requires more power than climb milling.

- Surface finish is worse because chips are carried upward by teeth and dropped in front of cutting tool. There’s a lot of chip recutting with conventional milling. Flood cooling can help!

- Conventional milling is preferred for rough surfaces.

- Because tool deflection is parallel to the cutter path with Conventional Milling, it can often produce a better surface finish. Try Climb Milling when roughing and Conventional on the finish pass.

- Climb Milling:

- Chips are dropped behind the cutting tool–less recutting and better surface finish with Climb Milling.

- Less wear, with cutting tool life being up to 50% longer with Climb Milling.

- Improved surface finish because of less recutting.

- Less power required.

- Climb milling exerts a down force during face milling, which makes workholding and fixtures simpler. The down force may also help reduce machining chatter in thin floors because it helps brace them against the surface beneath.

- Climb milling reduces work hardening.

- Tool deflection during Climb milling will tend to be perpendicular to the cut, so it may increase or decrease the width of cut and affect accuracy.

- If you're cutting over half the cutter diameter stepover, Climb Milling can result in negative rake cutting geometry. Try Conventional Milling in this case.

FREE FEEDS & SPEEDS MASTER CLASS: Learn What the Experts Know >

What is Climb Milling vs Conventional Milling (Down Milling vs Up Milling)?

Wondering whether to Climb Mill or Conventional Mill? Or perhaps wondering what each one is and what it does? You're in the right place!

The traditional approach is that CNC'ers are always Climb Milling and Manual Machinists are always Conventional Milling. It's probably true that Manual Machinists should stick to Conventional Milling as their milling style because the backlash of their machines makes it dangerous to Climb Mill.

But, CNC'ers should know that there are times when the climb milling process is the preferred way and there are times where the conventional milling process works better. Before we get into when to use each, let's have a quick definition of the differences in each cutting process.

First thing to note is terminology. Some will say "Climb Milling vs Conventional Milling" while others say "Down Milling vs Up Milling". They're one and the same cutting process:

- Climb Milling = Down Milling

- Conventional Milling = Up Milling

The difference between Conventional and Climb Milling is all about the relationship between the tool and the workpiece.

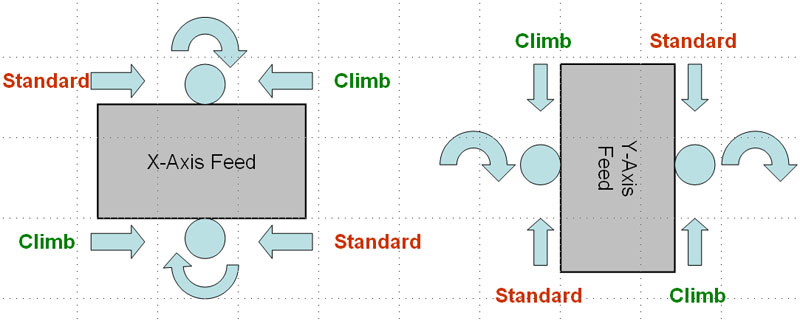

Climb milling is when the direction of cut and the way the cutting tool rotates combine to try to "suck" the mill up over (hence it's called "climb" milling) or away from the work. Here is a diagram showing conventional and climb milling for a number of orientations:

Arrows show workpiece motion, not spindle motion!

Keep in mind that for this illustration, it is the workpiece that moves, not the spindle. On some machines, like a gantry router, the spindle moves, so the labels would reverse. I keep it straight by thinking of the spindle as a pinch roller that can either help move the workpiece in the direction it was already going (climb milling), or that might fight that movement (standard or conventional milling).

Try the experiment on your milling machine of cutting with both millng methods and you'll see that climb milling is a lot smoother and produces a better surface finish (most of the time, there are times when conventional milling gives a better finish, see below) than conventional milling. Note that depending on which way you are milling, you will need to make sure your workpiece is supported well in that direction.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Conventional Milling vs Climb Milling

Advantages of Conventional Milling (Up Milling) cutting process:

-

The width of the chip starts from zero and increases as the cutting tool finishes slicing with conventional milling.

-

The cutting edge meets the workpiece at the bottom of the cut when conventional milling.

-

Upward forces tend to lift the workpiece during conventional milling.

-

Conventional milling requires more power than climb milling.

-

Surface finish is worse because chips are carried upward by teeth and dropped in front of cutting tool. There's a lot of chip recutting with conventional milling. Flood cooling can help!

-

Conventional milling is preferred for rough surfaces.

-

Tool deflection during Conventional milling will tend to be parallel to the cut (see the section on Tool Deflection for more).

Advantages of climb milling (Down Milling):

- The width of the chip starts at maximum and decreases with Climb Milling.

- The cutting edge meets the workpiece at the top of the cut when Climb Milling.

- Chips are dropped behind the cutting tool-less recutting and better surface finish with Climb Milling.

- Less wear, with up to 50% longer tool life with Climb Milling.

- Improved surface finish because of less recutting.

- Less power required.

- Climb milling exerts a down force with a face mill, which makes workholding and fixtures simpler. The down force may also help reduce machining chatter in thin floors because it helps brace them against the surface beneath.

- Climb milling reduces work hardening.

- It can, however, cause chipping of the cutting tool when milling hot rolled materials due to the hardened layer on the surface.

- Tool deflection during Climb milling will tend to be perpendicular to the cut, so it may increase or decrease the width of cut and affect accuracy.

So what's the preferred method? The fact that it gives much longer tool life so much is almost reason enough to stick to the climb milling process. But do consider the other advantages and disadvantages as there are cases where Conventional Milling wins big

FREE FEEDS & SPEEDS MASTER CLASS: Learn What the Experts Know >

Climb Milling Backlash

There is a problem with the climb milling process, which is that it can get into trouble with backlash if cutting tool forces are great enough. The issue is that the table will tend to be pulled into the cutting tool when climb milling. If there is any backlash, this allows leeway for the pulling, in the amount of the backlash. If there is enough backlash, and the cutting tool is operating at capacity, this can lead to breakage and potentially injury due to flying shrapnel.

For this reason, many shops simply prohibit climb milling at all on any manual machines that have backlash. They always use the conventional milling process as the necessary milling style. Some modern machines even came equipped with a "backlash eliminator" whose primary purpose was to enable climb milling and its attendant advantages.

One way to think of it is to consider the concept of chip load. This is a measure of how much material each tooth of the endmill is trying to cut. Typical values for finish work would be 0.001 to 0.002" per tooth. For roughing work, that might increase to 0.005". Now in the worst case, climb milling may grab the table and slam the work into the cutting tool by the full amount of backlash during the instant when a single tooth is cutting.

You can therefore add the backlash to the chip load to see what your new effective chip load might be in this worst case. Suppose you are roughing 0.005" per tooth and have 0.003" backlash. In the worst case, your chip load will soar to 0.008". That's probably not the end of the world, but it is a strain.

Now suppose you have an older machine with 0.020" of backlash and are running an 0.005" chip load. If the worst happens there your chip load will soar to 0.025", which is probably going to break the endmill and is very dangerous.

The second thing to consider is whether cutting forces are strong enough to pull the table through the backlash in the first place. A lot will depend on the exact cutting scenario together with your machine.

If you've got a fancy low friction linear way machine, it can grab easily. If you've got a lot of iron in the table, and maybe you're running with the gibs tightened a bit, it'll be harder.

There are ways to calculate the cutting tool force, but in general, smaller end mills, less depth of cut, lower feeds, and lower spindle speed will all reduce the cutting force and make it less likely the cutting tool can drag the backlash out of your table and create a problem.

In general, CNC machines shouldn't have any noticeable backlash, so these are more concerns on manual machines.

Under Certain Conditions, Climb Milling Produces Negative Cutting Geometry

So far, you've probably gotten the idea that maybe you should always be climb milling on cnc milling operations. After all, it leaves a better surface finish, requires less energy, and is less likely to deflect the cutter. Conversely, manual machinists are often taught never to run climb milling because it's dangerous to do on a machine that has backlash. The truth is somewhere in the middle. ABTools, makers of the popular AlumaHog and ShearHog cutters, point out some worthwhile rules of thumb:

- When cutting half the cutter diameter or less, you should definitely use climb milling (assuming your machine has low or no backlash and it is safe to do so!).

- Up to 3/4 of the cutter diameter, it doesn't matter which way you cut.

- When cutting from 3/4 to 1x the cutter diameter, you should prefer the conventional milling process.

The reason is that cutter geometry forces the equivalent of negative rake cutting for those heavy 3/4 to 1x diameter cuts. This is definitely not the best for Tool Life!

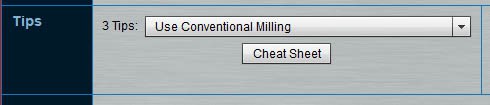

It seems that Dapra corporation first discussed this phenomenon way back in 1971. G-Wizard now reminds you with a little hint which one you should prefer:

G-Wizard's Hints tell you what to do: "Use Conventional Milling"...

If you've never played with our G-Wizard Speeds and Feeds software, take a moment right now to sign up for the 30-day trial.

Tool Deflection and Cut Accuracy in Conventional Milling and Climb Milling

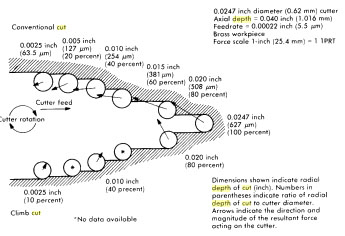

How does climb vs conventional milling affect tool deflection and accuracy?. The following illustration contains small arrows (often called vectors) showing the direction of tool deflection and cutter forces as the cutter moves along the toolpath:

The arrows show where the cutting force is attempting to deflect the cutter. Conventional cut at top, climb cutting at bottom.

Note how the deflection force vector is more nearly parallel to the cut with conventional milling (albeit the arrows are longer, showing there are higher cutting forces). With climb milling, the arrow is nearly perpendicular to the cut. If your cutter deflects 0.001", wouldn't you prefer it to be nearly in the direction of travel?

The alternative is for the cutter to plow deeper into the wall or pull away from the wall. Either case will introduce more error in the part being machined. The counterpoint is that the lengths of the vectors are longer when conventional milling. That's telling you that the cutting forces are heavier and the tool is more likely to deflect with conventional milling.

Try climb for roughing, because you can rough faster and the tool deflection effects on accuracy don't matter-the finish pass will deliver the accuracy. You can rough faster because cutting forces are lighter and the thick-to-thin chip profile carries the heat away on the chip.

That thick-to-thin + carrying the heat away is particularly crucial for tough work-hardening materials like stainless. It also results in a nicer surface finish if you can afford to climb for the finish pass.

Consider Conventional Milling for Finish Passes

This one is counterintuitive for a lot of machinists who are trained for most of their careers that climb produces a better finish than conventional. All other things being equal, that's true, but all other things are seldom equal!

The problem is that deflection affects surface finish too. If the vector is nearly parallel to the path, you can consider that the portion of the vector that pushes it "off parallel" is very small. Therefore, the tool will have little tendency to deflect and put waves on the wall you're finishing. Note that this may be particularly important with thin walls work where the walls are weak!

Therefore, you should switch to conventional milling for the finish pass if you're at all deflection challenged (use G-Wizard to see if your tool diameter and stickout result in small enough deflection for your finish pass). At the very least, one should avoid too much depth of cut when climb milling to create less tool deflection.

Another possibility is to go through the whole cutting process using a Climb Cut, and then do a final "ghost pass" or "spring pass" that uses the same depth of cut as the final climb cut finish pass, but is run as a Conventional Cut. Any material removed during this spring pass machining will be as a result of the tool deflection of the Climb Cut pass.

The same article suggests that when deflection is to be minimized, use no more than 30% of the diameter of the cutter for conventional milling and 5% for climb milling. Of course here again, if you have G-Wizard, you'll know what kind of deflection to expect and whether it's a worry.

Climb cut to rough and conventional to finish is in line with the consensus on cutting process over at Practical Machinist as well.

Properly managing deflection can help you avoid the need for an extra spring cut, which saves time and money.

I would continue to Climb Mill a Chamfer Mill or Roundover Mill because they can be a bit chattery and the reduction in cutting force helps minimize that.

Consider Conventional Milling When Micromachining

For all the same reasons, but considering deflection is much worse micro-milling, you should prefer conventional over climb milling most of the time when micro-milling. The biggest Tool Life issues when micromilling are runout and deflection.

It's a bit of a tradeoff whether the reduced cutting forces (and hence reduced deflection) of Climb Milling benefit Tool Life more than the direction of deflection for Conventional Milling, but the latter wins out. Check out our Micromachining page for more information on this cutting process.

Conclusion

The decision of whether to Climb Mill or Conventional Mill is more complex than most machinists know, but now you're equipped to decide which is the best milling style.

Climb vs Conventional Milling FAQ

What are the disadvantages of Climb milling?

The disadvantages of climb milling are:

- Climb milling can cause chipping in hardened materials.

- While tool deflection is less likely, it will be in a direction perpendicular to the cut. So if you're getting tool deflection, the accuracy and surface finish will be worse with climb milling.

- Climb milling cannot be used on machines with significant backlash, which includes most manual milling machines.

What are the disadvantages of Conventional milling?

The disadvantages of Conventional Milling are:

- Tool wear may be increased as much as 50%

- Surface finish is worse because chips are dropped in front of the cutter forcing a lot of chip recutting.

- Conventional milling requires more power than climb milling.

Is it better to climb mill or conventional mill?

If you're doing manual machining, the backlash of the machine probably limits it to conventional machining. With CNC, climb milling is often preferred. The exceptions when it is better to conventional mill are:

- When milling rough or hardened surfaces.

- If your cut width is 3/4 of the diameter or more. Climb milling produces negative cutting geometry in these cases.

- When the finish pass is tool deflection-challenged, prefer conventional milling.

- Conventional milling is often preferred when Micromachining.

Why does climb milling give better finish?

One of the biggest reasons climb milling gives better finish is that chips are dropped behind the cutter, resulting in less chip recutting. With conventional milling, the chips drop in front of the cutter, which maximizes chip recutting. Second, cutting forces are reduced which can mean less tool deflection and therefore less undulation in the wall of the cut. However, in cases where tool deflection is significant, conventional milling can give a better finish than climb milling.

Why climb milling is less recommended when using an old milling machine?

The problem is that the old machines often have significant backlash. When climb milling, the tendency of the cut is to pull the cutter deeper into the cut. The amount the cutter can be sucked in is equal to the backlash on the machine. If there is significant backlash, you will often break the cutter.

What is another name for climb milling?

Climb milling is also called down milling.

Which milling process is preferred for longer life of cutting tools?

Down Milling or Climb Milling is the preferred process to maximize tool life. The exception to this rule would be in work hardening materials which are more prone to chipping with climb milling.

What is conventional milling also known as?

Conventional Milling is also known as Up Milling. `

FREE FEEDS & SPEEDS MASTER CLASS: Learn What the Experts Know >

Be the first to know about updates at CNC Cookbook

Join our newsletter to get updates on what's next at CNC Cookbook.