What features would you include if you were to design the perfect CNC mini mill for your home workshop?

We'll take a look at that in this multi-part series which is aimed at helping the DIY CNC crowd get a handle on some of the up-front design considerations they should be thinking about for their CNC Mill conversion projects. In this first part, we'll consider criteria for choosing which donor machine to start with.

Donor Mill Considerations

First thing in a CNC Mill project is to choose the donor mill the conversion to CNC will be based on. There are three important considerations if you could choose any donor mill to start from:

1. Mass and Rigidity

2. Spindle

3. Bed mill versus knee mill

Let's cover each of these in turn.

Mass and Rigidity

We want mass and rigidity because machine tools thrive on it. Commercial VMC's weigh thousands of pounds. If your machine lacks sufficient rigidity, you'll be limited in terms of the size cutters you can use and how quickly you can machine. This may not matter for many hobbyists-we've all seen amazing work done by machinists on little Taig and Sherline mills. But, all other things being equal, we'd like the biggest mill our budget and space will fit as a starting point.

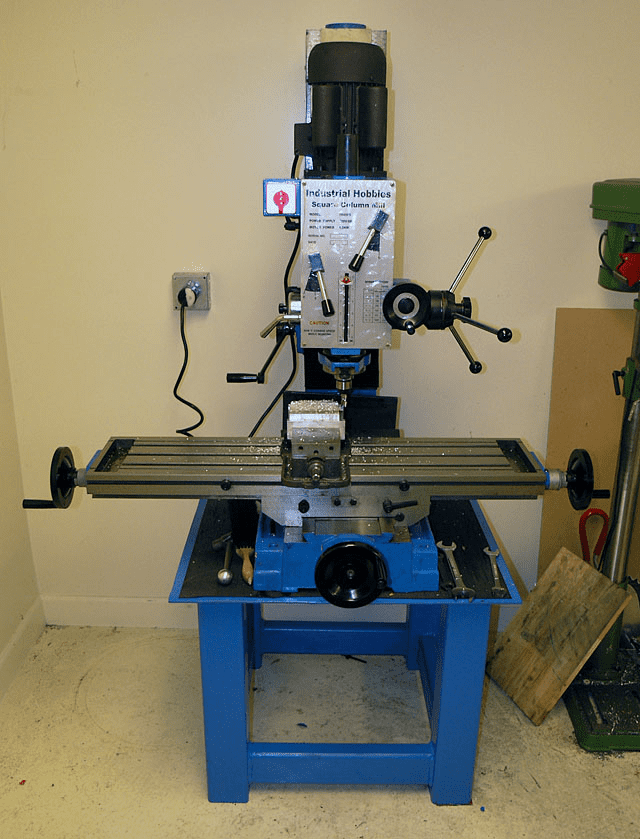

Two great choices from a mass and rigidity standpoint would be an RF-45 milling machine like my Industrial Hobbies mill, or for a G0704 like Hoss is doing so well with. The G0704 is more compact than an RF45, but it retains most of the capability of the larger machine. If you don't have room for an RF45, by all means go for the G0704 and don't look back. But, if you do have room, I like the bigger machine. If nothing else, it has more travels and more mass. Still, the G0704 is very capable, and with Hoss working so diligently at modding his, they are probably even better supported for do-it-yourselfers than RF-45's. I'm going to proceed on the RF-45 path for these articles, but you can find most of what I mention for the G0704 milling machine over on Hoss's site about that machine.

What about the spindle?

The heart of any machine is its spindle. This is a case where the G0704 has got the RF-45's beat. A box stock RF-45 is typically limited to a maximum of 1600 rpm on its spindle. That's fine for steel, but it's not enough for aluminum and other software materials. To be sure, you can machine those materials just fine, but your surface finish and the rate at which you can machine them will be limited relative to a better spindle. In addition, the noise level of the gearbox on these machines has to be heard to be believed-ouch!

To understand what "better" means, we need look no further than the garden-variety Bridgeport mills or perhaps the Tormach mills. 5000-6500 rpm spindles make for much better metalworking machines. These are belt-driven spindles rather than gear-driven, and hence they're much quieter too. All those gear ratios are not very conducive to CNC-controlled spindle rpms either, whereas a belt drive with perhaps 2 pulley ratios for a wider torque curve is perfect for VFD spindle rpm control. A good way to come to grips with what your spindle's specs ought to be is to make a list of machining operations. Then, you can use our G-Wizard Calculator (perhaps on free 30-day trial) to evaluate the RPM and horsepower requirements needed for those operations.

Here's a simplified form of such an analysis:

- Cut aluminum, steel, or plastic with each of these tools

- Slot with a 1/2" endmill up to 1/2" deep cut.

- Profile with a 1/2" endmill and 15% of diameter width of cut.

- Do fine profiling, finishing, and detail work with a 1/8" endmill.

- Drill holes with a twist drill up to 3/4" in diameter.

- Run a 2" Facemill

It's important to cover a bunch of different scenarios like that due to the different needs of the different tools. Facemills and big Twist Drills use a lot of power, but often may not require too much rpm. A 1/8" endmill doesn't need much power, but it wants to be spun pretty fast for best results. Steel uses much less rpm than aluminum and especially less than plastic. Using G-Wizard, you can find out the rpm and power requirements quickly for an array of these scenarios. Be sure to note down the recommended feedrates too, as you can use those in choosing your motion control components-steppers, ballscrews, pulley ratios for cog belts, and so on.

You don't want to skip this analysis step. Typical metal-working CNC mills are fairly forgiving, but I get notes all the time from DIY CNC Router builders who have mismatched a high speed spindle with low feedrate motion control and are having a hard time making the feeds and speeds work. There are tricks you can do to help, but doing a little bit of up-front thinking to make sure you machine will be good at what you need it to do is even better. It's always cheapest to fix problems at the design stage rather than discover them when the machine has already been built.

In addition to the spindle's rpm capabilities, you'll want to consider which spindle taper to choose. In machines of this class, the most common tapers are R8 and Morse tapers. I much prefer the R8, which has become somewhat ubiquitous for machines in this class. Decent quality tooling is abundant and fairly cheap. It's also well understood how to do things like create powered drawbars and tool changers for R8 tapers.

Since we're talking about "ultimate" benchtop CNC machines here, I will also mention 30-taper spindles. They're much rarer, but they are out there for this class machine, at least for the RF-45 machines. The NMTB and BT-30 toolholders are substantially beefier and setup from the get-go to be compatible with a tool changer. They're going to be more expensive, but I'd consider them superior to R8 spindles if you have the option. Spindle cartridges are available in 30 taper from places like Tormach. You're going to have to do pretty major surgery on your RF-45 to convert it to a belt-drive anyway, so perhaps coring out the head and installing a new spindle cartridge gets you enough bang to justify the bucks. FWIW, I will be installing a Tormach 30-taper spindle cartridge in my RF-45 mill.

I will have more to say about spindles in a future installment, mostly in terms of pulley ratios, power curves, VFD's, and the like. That's nearly all going to be add-on work that's done after you get the basic CNC motion control working and you're operating the spindle by hand, so we can wait a bit before digging into it.

Why not choose a knee mill?

Let's put aside the idea that this article is about "Benchtop" milling machines, and the classic Bridgeport clones are way too big for a bench. An RF-45 on a dedicated bench such as pictured above might as well be a knee mill in terms of floor space needed in your shop. Most knee mills have a much more ideal spindle too than RF-45s. Plus, knee mills have more flexibility. For example, you can attach a very tall workpiece to the side of the table, let it droop almost to the floor, and swing the head over to work on it. Can't do that on a bed mill! Why not choose a knee mill?

Despite all that, I prefer "Bed" mills to "Knee" mills for CNC work. All the modern commercial CNC's are bed mills, which tells you something. The reason is that the additional flexibility of the knee comes at the cost of several things. The knee is heavy, so you wind up needing to motorize and CNC both the knee and the quill. Motorizing the knee alone it's hard to get it moving fast enough for the best CNC needs because it is so heavy. Dealing with 4 axes instead of three adds cost and complexity. Despite the knee being heavy, the spindle is mounted in such a way that knee mills are often not as rigid as you would expect for their size and weight. It's the price they pay for their flexibility. My RF-45 mill is every bit as rigid and then some as a much heavier Bridgeport. Lastly, knee mills are not cheap-they typically cost quite a bit more than an RF-45 or G0704. You're paying a lot for both their flexibility and their CNC shortcomings.

If you've already got a knee mill, then I'd say keep it and CNC it. It's not like you can't build a great CNC conversion starting with a knee mill. There were a lot of great CNC knee mills back in the day too, for example the Tree CNC Milling machines. But, if you have the luxury to choose any donor machine to start from, I'd choose a bed mill.

There is a class of bed mill out there that were being made for low end CNC milling knees that have Bridgeport clone spindles on them. They look like oversized RF-45's. Just get on eBay and do a search for "bed mill" to get an idea. One of these would be a fantastic starting point for a CNC mill project.

Other Considerations

A lot of the features on the donor mill don't matter too much as you will discard power feeds and other accessories. My #1 other consideration for choice of Donor Mill for someone starting out to build a DIY CNC Mill would be to look for the largest possible community of others who've converted the same mill. These are the people you'll be able to get help and guidance from on your project. Another aspect of support would be the availability of a CNC conversion kit. A mechanical only kit can save you a fair amount of time and typically they don't add that much cost to the project. I highly recommend them for beginners as you'll get your project up and running sooner with a kit than if you have to fabricate everything from scratch.

Look for decent quality ways and choose a clone of your machine style (there are usually many sources for nearly the same mill) that is a little better. Something like leadscrew quality won't matter though-you'll replace the leadscrews with ballscrews as soon as you can. A machine that has a way oiler would be a definite plus, but you can add an oiler to most any machine fairly easily too.

Conclusion

You've now got a framework of things to think about when choosing a donor mill for a DIY CNC Mill project. For our next installment, we'll take a look at the mechanicals involved in driving the axes: ballscrews, ballnuts, bearings, toothed belts, and motor mounts.

Be the first to know about updates at CNC Cookbook

Join our newsletter to get updates on what's next at CNC Cookbook.